May 16, 2023

– By Uyen Truong –

Domestic violence is a persistent issue affecting millions of people worldwide. Yet, it is extremely challenging for law enforcement to identify and intervene promptly, especially when domestic violence can emerge in various forms. The fight is even harder among Asian communities. The victims, predominantly women, are usually ingrained in the traditional beliefs that men hold power in the household and women must be submissive.

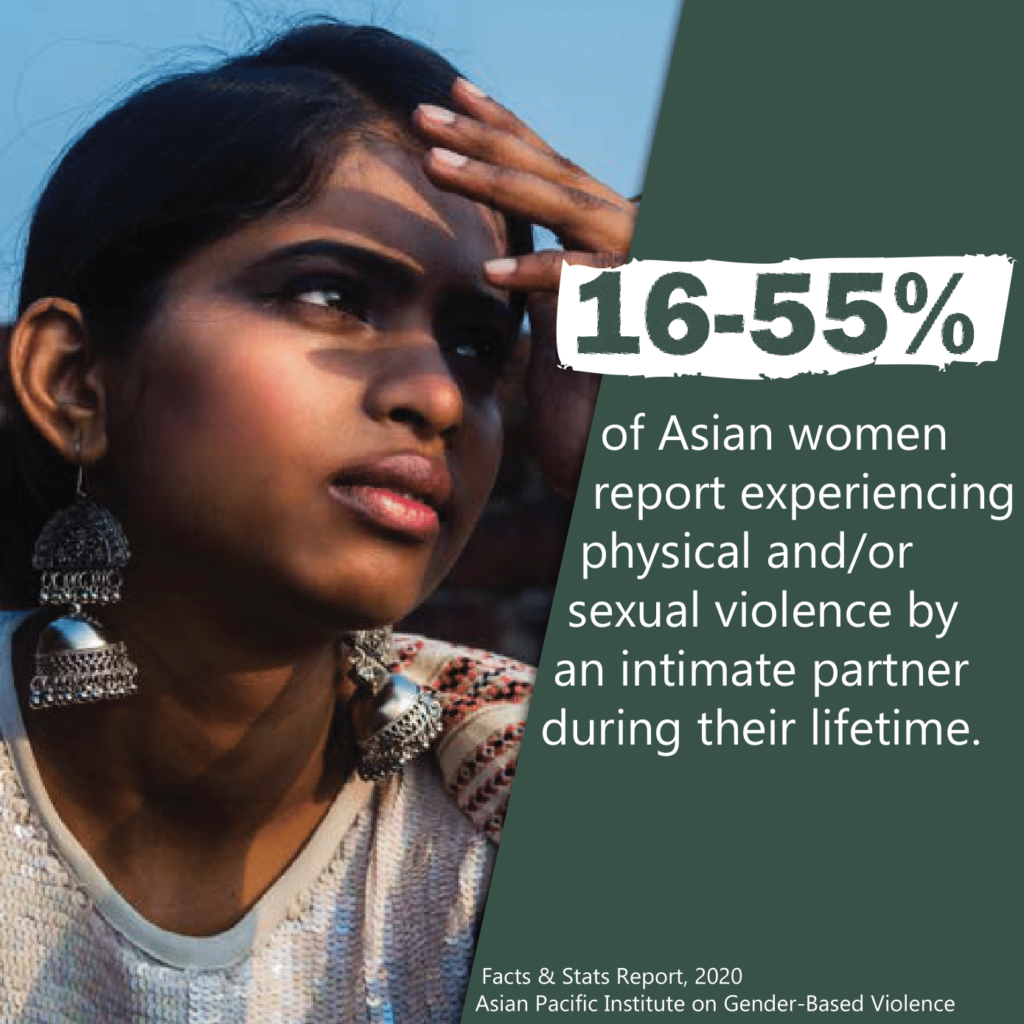

According to the Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence, 16-55% of Asian American women experienced intimate physical and/or sexual violence at some point in their lives. Yet, they tend to underreport their domestic violence experience compared to other races. This is due, in part, to the internalized gender norms and duties, the cultural values of prioritizing family and community over self, and the beliefs that spouse conflicts are private matters.

In one study, about 25%-33% of Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Cambodian American adults believed that wife abuse could be justified in certain situations. These situations could be a wife’s sexual infidelity, nagging, or refusal to perform household duties. These harmful beliefs not only normalize the husband’s abusive behaviors but also guilt the victims. This could make them reluctant to seek help and even blame themselves.

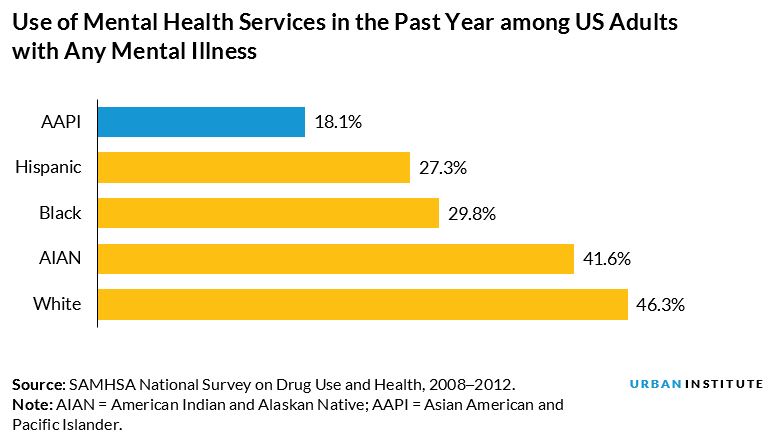

This guilt, as well as the stigma against mental illness, stress from being in a new culture, and language barriers, worsen the effects of domestic violence on the victims’ mental well-being. Several studies have shown similar patterns of severe depression and anxiety disorders in populations of South, Southeast, and East Asian immigrant women who have experienced intimate partner violence.

Partner violence affects both your mental and physical health. Research shows that survivors of intimate partner violence tend to suffer from chronic pain, stomach issues, heart diseases, and weaker immune systems. Stress and trauma resulting from domestic violence can increase inflammation, imbalanced hormones, and disruptions in how your body handles stress. This in turn causes severe anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and may lead to harmful behaviors such as smoking, binge drinking, and sexually risky activity.

A global problem on a local level

Kim-Lien Tran is a Community Liaison for the Equitable Neighborhoods Initiative. She has been working as a health educator with the Vietnamese community in Bayou La Batre, Alabama, for more than 10 years. She has focused much of her efforts on the women of her community. Through personal experience and stories from the women she works with, Kim offers valuable perspectives on the mental health of Vietnamese women in her community. A significant percentage of these women have lived in constant fear of safety from both outside and within their homes.

According to Kim, the hardest part in the fight against partner violence is the “acceptance” mindset of the victims themselves. Kim found a common thread with many of the Vietnamese women she has been working with. Even though abuse clearly happened in the household, they do not perceive it as abuse. “They were brought up in the belief that once you’re married, you have to accept what is given to you, what is thrown at you,” said Kim, “but we need to move the women away from that way of thinking.”

As a woman who was also brought up in that mindset, Kim shared that it took her a lot of time to realize that partner abuse of any kind is not normal and is unacceptable. Educating Vietnamese women about domestic violence requires a significant amount of time and patience, but is a crucial first step in rescuing the victims from their toxic relationships. It is tough for local authorities and support programs to intervene if the victims trivialize their abuse experience and cover up their partner’s violence.

They [the women] take care of everything – their spouse doesn’t do anything except go to work, come home, and think that bringing back the money is enough.

Kim-Lien Tran, bayou la batre community liaison

Another factor that makes Vietnamese women hesitate to stand up against their abusive partner is the lack of trust in their capabilities to be independent. These women were taught that they must be subordinate to their spouses both educationally and financially. They were taught that the husband must be the breadwinner, worrying about nothing but making money. The wife is expected to be a homemaker, staying behind her husband to set him up for success.

This belief has been internalized by many Vietnamese women. They think that they would be nothing without their husbands. “But little do they know that they are independent already,” said Kim. “They [the women] take care of everything – their spouse doesn’t do anything except go to work, come home, and think that bringing back the money is enough,” she elaborated.

In her workshops with the women in the community, Kim said she constantly reminds her trainees that they are more powerful and independent than they think they are. Kim believes there needs to be more effort put into strengthening women’s self-confidence. She says self-confidence is an important determining factor of whether they report partner violence and seek help.

Curating care to the individual

Kim has been working actively with Vietnamese girls and women in her community as a community health worker and as an ENI Community Liaison in Bayou La Batre. She educates them about domestic violence and the importance of mental well-being. In her earlier Summer Youth Program, Kim invited a counselor to come and talk to the young girls about healthy relationships. Kim knows each girl individually, so she helped the counselor to personalize the mental health check-ins. Kim has noticed that the home environment and the parents’ mindset, especially the mom’s, greatly impact the girls’ perception of a healthy relationship. Although the younger generation is generally more open-minded about gender norms, she still sometimes sees the old thinking in the girls. She believes this usually comes from their traditional-minded moms.

Kim shared that it takes more patience and empathy for the older generations of women to open up about their mental well-being and their relationship with their partners. “The best thing to help the women here is to let them talk,” said Kim. Occasionally, Kim hosts casual gatherings with the women just for them to have some fresh air outside of their stressful homes. “We ate, but we talked also,” she proudly recalled. For Kim, this is the most effective approach to weave in heavy topics like mental health and partner violence. “Sometimes, I just need one person to open up, and the conversation starts,” Kim shared.

These casual get-togethers act as an efficient way for Kim to communicate educational information to the community. But they are also an opportunity for Kim to listen to whom she serves. Through these conversations over the dining table, Kim learns more about other sources of stress that intensify the effects of domestic violence on the ladies’ mental health. One stressor has been COVID-19.

A global pandemic intensifies isolation

“COVID-19 makes everything worse.” Recalling the COVID-19 lockdown period, Kim couldn’t help but express the struggles many of her trainees have gone through. The restrictions on social gatherings made them unable to go outside and socialize with other women. This made it harder for them to get a break from their stressful homes. One of the women shared with Kim that every day, she would find excuses to get away from her husband for a while. During COVID-19, she couldn’t anymore. It was even more overwhelming and exhaustive for these women when their abusive spouses now stayed at home instead of going to work.

According to the American Journal of Emergency Medicine, domestic violence cases against women increased by 25-33% globally during the pandemic. The lack of opportunity to escape was not limited to a physical issue. The women also felt trapped mentally when the supporting programs were limited to remote only. In Kim’s community, all her assistance programs had to move from in-person to phone calls. Occasionally, Kim would receive a phone call at nighttime from some of her trainees, “Can I just talk to you? I don’t know who else to talk to.”

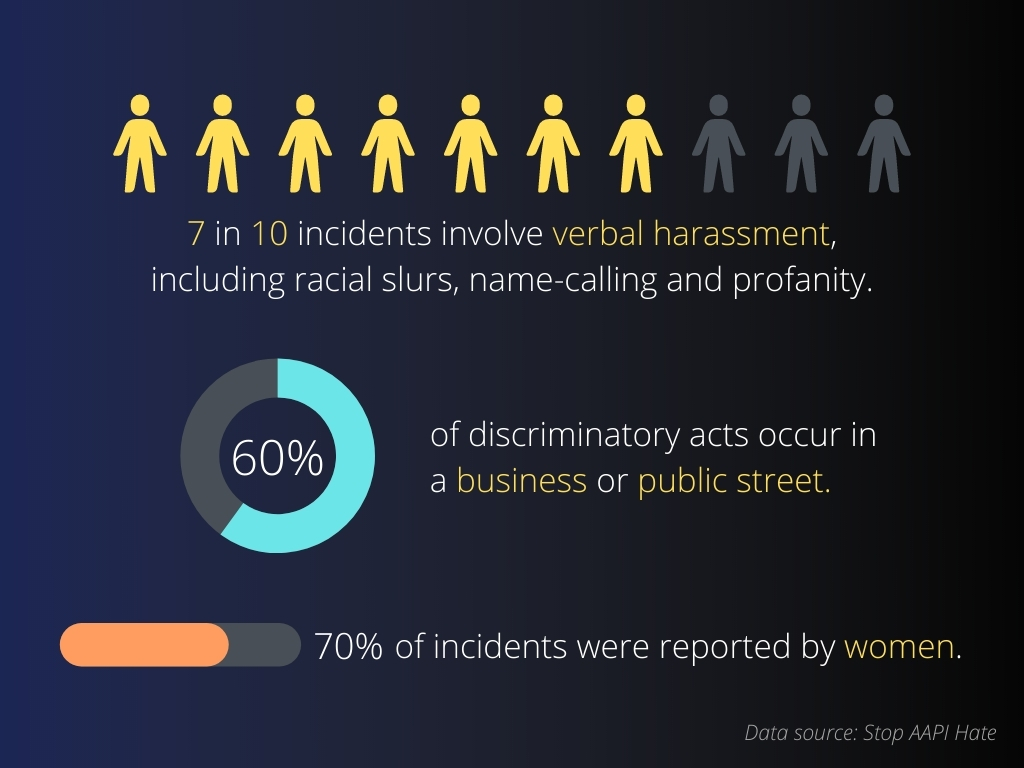

During the pandemic, many Vietnamese women’s fear of safety did not stop at intimate partner violence. Anti-Asian racism, a formerly overlooked concern, suddenly surged in visibility and hostility. This hatred and violence terrorized the Asian communities, adding another layer of fear for women who had already been victims of home violence.

According to Stop AAPI Hate, nearly 3,800 Asian-hate incidents were reported from March 19, 2020, to February 28, 2021, nationwide. Sixty-eight percent of these cases were women. Being followed on the street, stared at with disdain, or yelled racist slurs over the car window are some of the common incidents that happened to the Vietnamese women and Kim herself during and even after the pandemic.

“They [the Vietnamese women] kept it close; they only went to the Asian stores, and even if they needed to go to places like Walmart, they would just hurry up and only get what they need,” Kim shared. Many of Kim’s trainees still feel anxious whenever they go out. Some won’t leave the house once the sun sets. “They are [afraid] of being attacked,” Kim noted, underscoring the long-lasting effect of violence on the women in her community.

The pandemic has been alleviated and people have been getting back to their normal lives. But the trauma left on the Vietnamese women in Kim’s community, especially the ones that have been through domestic violence, is hard to relieve. “At some point, I will do just a sit-down with the community, especially my women,” Kim said. “COVID is not that bad anymore, and people can go out freely, but who knows if, in the back of their minds, they still have worries about going out and getting attacked.”

Kim also noted that sometimes, it’s hard for her trainees to admit that traumas like COVID-19 or domestic violence can greatly affect their mental well-being. The thinking that “mentally ill is crazy” or “a slap once in a while is not domestic abuse” remains the biggest roadblock for Kim to get her mental health resources in the women’s hands. For Kim, the problem is not whether the mental health resources are available, but more of how to make sure her community is aware of these resources and actually uses them. Overcoming the stigma about seeking help, especially mental health care, is the long-term goal of Kim’s work in her community.

To learn more about domestic violence in Asian communities and how to support victims, read more about when Kim spoke with us about Domestic Violence Awareness Month.

If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence, there are many resources to seek help. Kim mentioned a few in Mobile County, Alabama:

- Penelope House in Mobile, AL, is a shelter that can provide refuge for victims and their children when their lives are in imminent danger. This temporary shelter allows people to escape from a violent situation. They also have a 24-hour crisis line at 251-342-8994.

- Lifelines Counseling Services in Mobile, AL, is another resource for someone in a domestic violence situation seeking help. Lifelines Counseling has a Rape Crisis Center and 24/7 Victim Services at 251-473-7273 or 800-718-7273. This hotline is answered by trained staff and volunteer advocates.

Other resources for support:

- The Center for the Pacific Asian Family and Asian/Pacific Islander Domestic Violence Resource Project offers 24-hour multilingual hotlines with more than 20 languages.

- The National Domestic Violence Hotline is available 24/7 by calling 1-800-799-SAFE (7233) and has over 200 languages available through interpretation. You can also visit www.thehotline.org or text LOVEIS to 22522.