October 27, 2022

– By Erin Hackenmueller –

Every October, the U.S. honors Domestic Violence Awareness Month (DVAM). Domestic violence (also called intimate partner violence, domestic abuse, or relationship abuse) is a pattern of behaviors used by one partner to maintain power and control over another partner in an intimate relationship. 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have been physically abused by an intimate partner, according to the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

DVAM brings victims, survivors, advocates, and supporters together to end domestic violence for good.

I spoke with Kim-Lien Tran, an ENI Community Liaison and an employee of Boat People SOS (BPSOS) in Bayou La Batre, Alabama, about domestic violence in Asian American communities. Kim works with many immigrants and immigrant families, many of whom are from Vietnam, that live in Mobile County near Alabama’s gulf coast.

Q: What is the purpose of Domestic Violence Awareness month?

KLT: The purpose of Domestic Violence Awareness Month is to make people aware that a lot of domestic violence goes unnoticed and that it’s an ongoing problem that we must do something about. We can honor DVAM by bringing awareness of domestic violence to the forefront on social media, at church, in Bible study classes, and in our communities.

Q: How can people support survivors of abuse?

KLT: We can help support the survivors by letting them know that they are not alone. We can be their voice for them. We can also check up on the survivors from time to time to let them know that we are there for them even after they are safe and settled.

Domestic violence can impact anyone, regardless of gender, sexual orientation, race, or class. But people in marginalized groups are often disproportionately affected.

Up to 55% of Asian women living in the United States have experienced some form of physical or sexual violence in their lifetime, according to the Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence. For immigrants, language barriers and fears surrounding deportation can make these victims feel trapped in abusive relationships. According to the Tahirih Justice Center, immigrant women and girls are up to 2 times more likely to experience domestic violence than the general population.

The National Domestic Violence Hotline (NDVH) explains that Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities often face obstacles to reaching safety, like victim blaming, financial limitations, language barriers, immigration status, and cultural and religious expectations.

Language barriers can limit where someone can find support – national and local hotlines often don’t offer the languages needed to serve a diverse community. Kim often must provide translation services for survivors seeking support. Additionally, the NDVH explains partners who choose to abuse could use phrases like “Who will hire you? Your English is terrible!” or “Who else will take care of someone like you who does not speak the language?” which can create doubt and fear for the survivor.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, domestic violence calls surged for Asian American women. During the lockdown, people who chose to abuse were able to watch their partners around the clock and took away resources for women to seek help or leave, according to an article from NBC News and the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism. The article explained it was harder for AAPI women to leave the home, citing rising anti-Asian racism leaving women afraid to leave an abusive home and go in public, economic fallout because of the pandemic creating worries surrounding financial instability, and fear of the actual COVID-19 disease.

Q: How have you supported survivors of abuse within the Vietnamese community? Are there tactics that have been successful?

KLT: We support the survivors of abuse by being there for them every step of the way to get them through the rough times and to always let them know how strong they are. We have a support group to let them share their stories. Often Vietnamese people do not like to talk about domestic violence, or they pretend it’s not there. So, for people to really see and accept that there is domestic violence in our community, we have group discussions on domestic violence and let them tell us what they see or what domestic violence means to them. Then we talk about what domestic violence actually is and what it looks like.

Kim’s experiences working with survivors are found on a national level. The Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence explains that many AAPI women are expected to keep abuse in their family a secret, or if they choose to speak up, members of their family or community may protect the partner’s reputation.

Q: Is there any advice you would give about specifically supporting the Vietnamese or Asian American communities?

KLT: To support the Vietnamese or Asian American communities, we first must listen to them and understand them before we try to help. Each community is unique. They do things differently and see things differently. Not all Vietnamese or Asian American communities are the same.

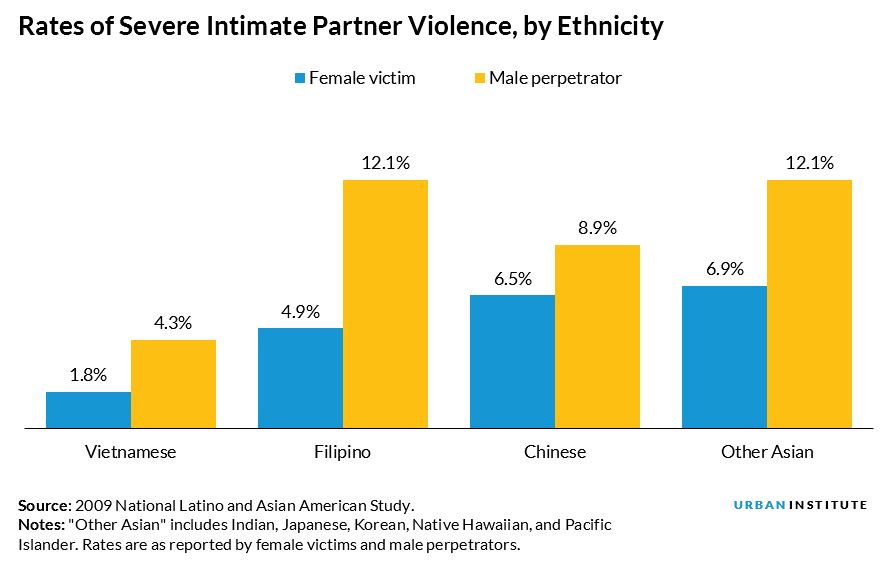

Kim is absolutely correct. AAPI people are not a monolith. This graph from the Urban Institute shows that reported rates of intimate partner violence among different ethnicities are very different, although it’s difficult to identify if the discrepancies are due to actual differences in occurrence or just differences in reporting behaviors.

If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence, there are many resources to seek help. Kim mentioned a few in Mobile County, Alabama:

- Penelope House in Mobile, AL, is a shelter that can provide refuge for victims and their children when their lives are in imminent danger. This temporary shelter allows people to escape from a violent situation. They also have a 24-hour crisis line at 251-342-8994.

- Lifelines Counseling Services in Mobile, AL, is another resource for someone in a domestic violence situation seeking help. Lifelines Counseling has a Rape Crisis Center and 24/7 Victim Services at 251-473-7273 or 800-718-7273. This hotline is answered by trained staff and volunteer advocates.

Other resources for support:

- The Center for the Pacific Asian Family and Asian/Pacific Islander Domestic Violence Resource Project offers 24-hour multilingual hotlines with more than 20 languages.

- The National Domestic Violence Hotline is available 24/7 by calling 1-800-799-SAFE (7233), and has over 200 languages available through interpretation. You can also visit www.thehotline.org or text LOVEIS to 22522.