October 8, 2022

—By Debbie Quinn—

MONKEYPOX to be exact is NOT Chickenpox or Smallpox and you don’t get it by playing with monkeys. A pox is a pimple-like eruption or rash on the skin that can contain pus. While vaccines that prevent the smallpox are also at least 85% effective in preventing monkeypox, the diseases are different. So, with all of that said, why are we so worried about a 65-year-old virus that has a vaccine that can help eradicate it?

One reason could be that the smallpox vaccine was given regularly up until 1977. Now, the vaccine is no longer recommended because smallpox has been essentially eradicated from the world. There were some vaccines stocked up, but the world was slow in pulling them out of storage and thus arrived a little late to catch the first few hundred monkeypox cases. The global pandemic hasn’t helped either with people slow to go to the doctor or who might be embarrassed. Scientists who study disease feel that monkeypox has been flying under the radar for years in other parts of the world.

Monkeypox has been deemed a public health emergency of international concern, which is the World Health Organization’s highest alert level. “We have an outbreak that has spread around the world rapidly, through new modes of transmission, about which we understand too little,” WHO’s director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said. “For all of these reasons, I have decided that the global monkeypox outbreak represents a public health emergency of international concern.”

Signs, Symptoms, & Spreading

Monkeypox starts with symptoms that might feel like the regular flu. Common symptoms include:

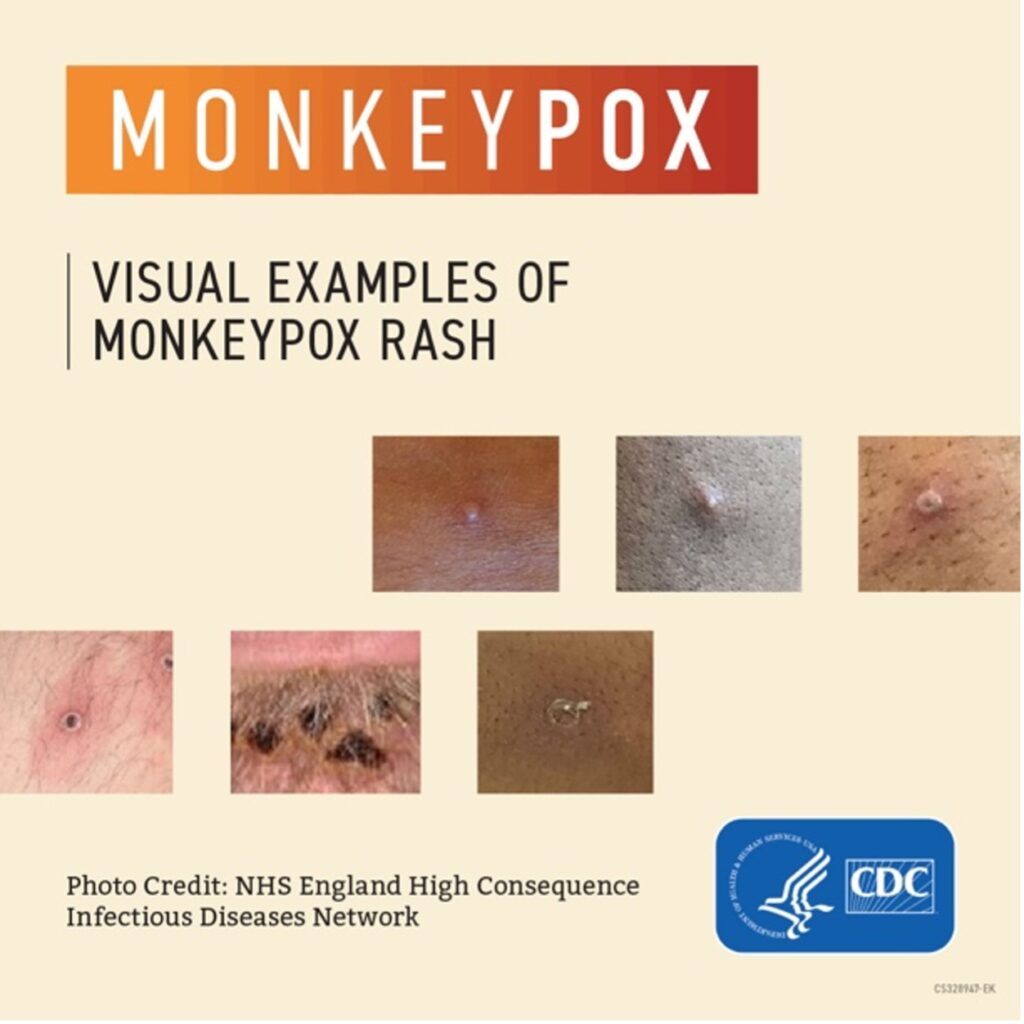

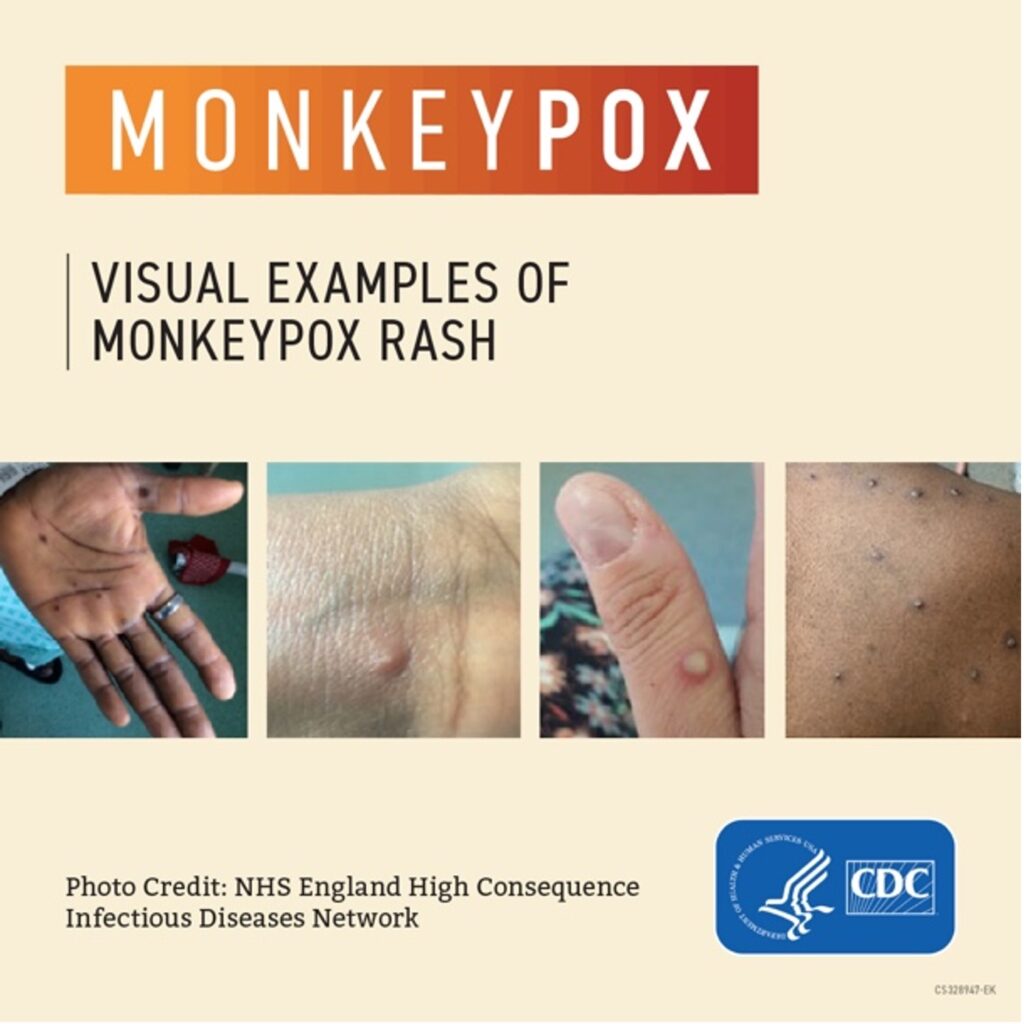

- Rash that may initially look like pimples or blisters and may be painful or itchy

- Fever

- Chills

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Exhaustion

- Muscle aches and backache

- Headache

- Respiratory symptoms (e.g. sore throat, nasal congestion, or cough)

People infected with monkeypox may experience all or only a few symptoms. The rashes typically develop after a few days, but sometimes rashes can be the first symptom. Monkeypox rashes can become very painful, and hospitalization may occur to help ease the pain. It can also cause permanent scarring.

During all the initial symptoms, the person is infectious. A person with monkeypox can spread it to others from the time symptoms start until the rash has fully healed and a fresh layer of skin has formed. The illness typically lasts 2–4 weeks.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Monkeypox can spread to anyone through close, personal, often skin-to-skin contact, including:

- Direct contact with monkeypox rash, scabs, or body fluids from a person with monkeypox.

- Touching objects, fabrics (clothing, bedding, or towels), and surfaces that have been used by someone with monkeypox.

- Contact with respiratory secretions.

Monkeypox doesn’t pass through casual contact, like shaking hands, a quick peck on the cheek or sharing a toilet seat. Most is passed through very intimate contact and has no respect for sexual or gender identity. This direct contact can happen during intimate contact, including:

- Oral, anal, and vaginal sex or touching the genitals (penis, testicles, labia, and vagina) or anus (butthole) of a person with monkeypox.

- Hugging, massage, and kissing.

- Prolonged face-to-face contact.

- Touching fabrics and objects during sex that were used by a person with monkeypox and that have not been disinfected, such as bedding, towels, fetish gear, and sex toys.

Children and adults alike can contract the disease, and pregnant people can give it to their babies in utero.

People who are immunosuppressed also need to be extra cautious. Individuals who have been diagnosed with cancer, HIV, and or who have an underlying skin condition such as eczema or psoriasis are extra susceptible to monkeypox. With any kind of break in the skin, the virus can find a strong hold and take advantage of it.

“If you have an underlying skin condition such as eczema—atopic dermatitis—the virus finds the places where you have the rash and it creates this very explosive necrotizing, devastating skin illness,” said American Medical Association member Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, Dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine, and professor of pediatrics and molecular and virology and microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Normally when we think of vaccines, we assume we need to get vaccinated before infection. But the monkeypox vaccine can work even if given after someone is exposed. The CDC recommends that people get vaccinated within four days of the date of exposure for the best chance of preventing the onset of the disease. One issue with monkeypox is that the first lesions or open sores can mimic other bacterial/viral infections. A lot of times it shows up around the genital region and patients and health care professionals might misdiagnose it as syphilis and it’s not treated correctly. Also, people may be hesitant to go to the doctor, to show it to anyone including a health professional. Seeking advice from medical professionals is important if you think you might have contracted monkeypox.

Contact Tracing is a very effective way to stop the monkeypox virus. Without that ability to go back and see where and with whom people have been intimate with or might have been in close proximity to, we can’t stop the next infections as easily. Medical professionals feel that most people are being very diligent about stopping this virus and have paid more attention to symptoms and rashes they may see.

History of Monkeypox

Monkeypox was first identified in a monkey in 1958, hence the name, but it didn’t start out in monkeys. The World Health Organization is trying to change the name to avoid confusion because humans do not catch it from monkeys. A type of squirrel or rodent in parts of central and western Africa have been identified as a carrier of monkeypox and can infect people who hunt or eat them, and then from those people to others.

Monkypox has been spreading in Africa for years. Outbreaks were initially limited to rural areas where people would hunt for food and come into contact with animals, but in 2017 it started spreading in unfamiliar ways into more populated areas. In much of the world, monkeypox hasn’t been severe and there have been no deaths. But in Central Africa, the strain of monkeypox they’re dealing with has a mortality rate of about 10%. Despite researchers in Africa dealing with outbreaks for years, most countries don’t have large stockpiles of vaccines. Dr. Dimie Ogoina, infectious-disease physician at Niger Delta University in Amassoma, Nigeria, is frustrated by monkeypox having been largely ignored by Western nations until now and worries that the current global outbreaks still won’t improve the situation for Africa. “If we don’t draw the attention of the world for this, a lot of the solutions will address the problem in Europe, but not in Africa,” he said.

In 2003, the US had their first monkey pox outbreak that was linked to contact with infected pet prairie dogs. These pets had been housed with Gambian pouched rats and dormice that had been imported into the country from Ghana.

But Monkeypox appears to be slowing its march around the world either through people being vaccinated or change of lifestyle. “We’ve started to see globally that we might be turning the corner,” Rochelle Walensky, MD, the CDC director, told the Wall Street Journal.

If there’s one thing I hope that we’ve learned is that public health is the bedrock of our nation. Public health workers are the first line of defense when a new and unfamiliar disease threatens our families.

Monkeypox may be here to stay along with COVID-19 and all the other types of diseases we have. Ask your healthcare provider your questions and become educated on your health risks.